III

Caracas: truth and fiction

“That emptiness that serves as a place”

Michel Foucault

“I take possession of this land, in the name of God and the King,” Diego de Losada declared when he founded the city of Caracas, on July 25th, 1567, describing it as he got to know it then:

“The city of Caracas has a location with such a heavenly character that, without competition, it is the best of all that America possesses. It seems spring chose it as its permanent dwelling, for, since it remains in the same temperance all the year, neither cold bothers, nor heat annoys. Its waters are many, clear and thin, because the four rivers that sufficiently surround it offer their crystals, for, without yet recognizing any heat of the summer, in the greater intensity of the heatwave they maintain their freshness.” *

The city we photograph is so far from Diego de Losada’s description. In the abyss of such a distance it is, at the same time, a sky of that sky, water of that water, a river of that river and, every day, a mountain of the same mountain.

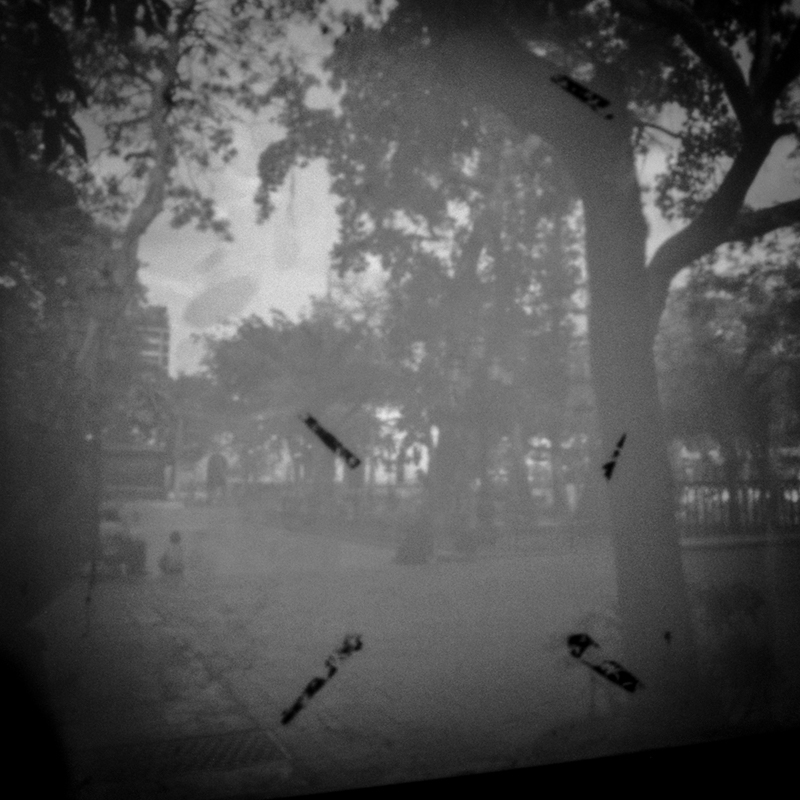

We stare at these appearances from the narrow hole of a pinhole camera. We are sheltered by its dark emptiness, its austere constitution —still an artifact— by the absence of optics and the demand for a lengthened time, longer than it is needed with a conventional camera. This extended time entails a greater contemplation, and then it is possible to get a halted pulse where we can truly be. The consequences of using this resource have been fundamental for our choosing it, but our commitment is not related to its technical aspect, but to the photographic fact, which returns in an image as culture, as language and as a trace. A sensitive making of where it is possible to grasp what is real of our city as a pure thought, without losing its reality as a fact, its expression, its appearance.

We do not try to catch the trace of the disappearing city, nor do we try to replace the already evaporated city with poignant images of a reality in constant combustion. We approach the urban space from our immediate time, and also from our personal and civic memory. Intermediaries, dialogical and aware of the impossibility of photography to reflect the world, but having the capacity of showing it as we perceive it in a specific time frame that, besides, is mutant.

We know that it is not possible to restore the everyday city we long for, or that city we do not know still —the city of tomorrow, the one that has not yet arrived— because our glance and those resources we use take place according to the human sense that makes up both, our need and our desire. We photograph something that exists: in its beauty, its horror, its vitality and its decline.

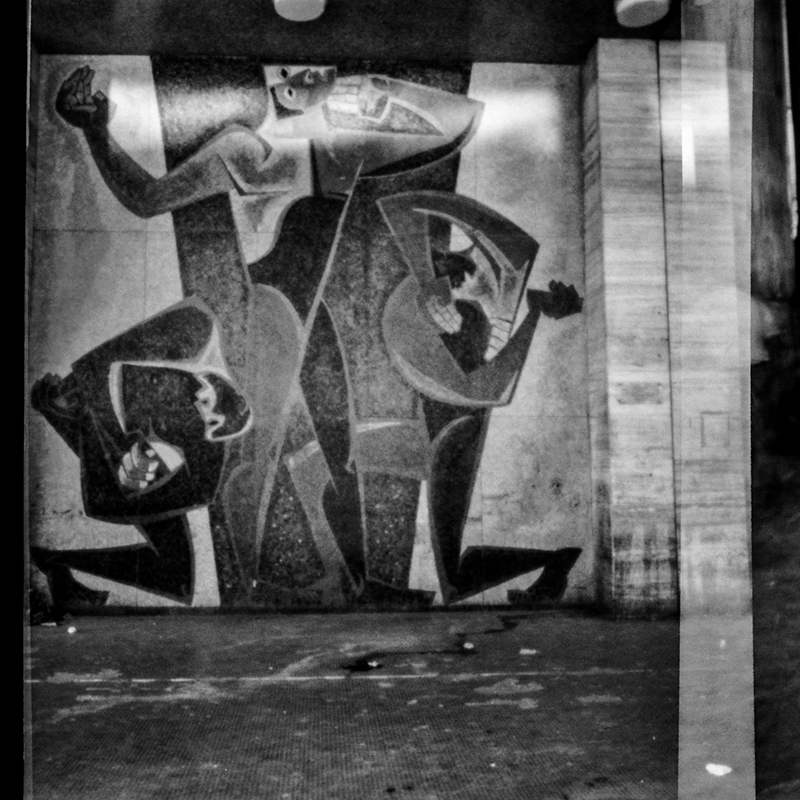

Sometimes, images return with a hidden thought, like that creation that follows destruction or death. We amaze at the autonomy and mystery of those sparkling and illuminating metaphors that cover of dawn, though briefly, the night that has already devoured us. That daily and atrocious violence that shares the landscape with us is not secret, but we are grateful for the redeeming possibility of the image to relieve us in its occurrence.

We find space in that disappearance, far from geographical or bonding exercises. We do not move from north to south, or from east to west. We move from mountain to darkness, from architecture to religion, from people to forest, from clouds to branches. “So heavenly”. So luminous.

Laura Morales Balza

* Carmen Clemente Travieso. Las esquinas de Caracas (2001). Caracas: Editorial CEC, SA. Los Libros de El Nacional.